‘It keeps me up at night’: Inuit leader Natan Obed presses for climate change action | CBC News

The middle of June was still ice fishing season when Natan Obed was a kid growing up in Nain.

Now in his 40s, Obed said fishing now is just a five-minute walk down to the ice-free shore.

“There just isn’t ice at all in the middle of June, around Nain. And we’re catching fish along the shoreline, just up in the harbour.… In my lifetime, I’ve gone from harvesting by using the sea ice to harvesting by walking out my door,” he said.

The 2020-21 ice season has been an extraordinary one in Nain and all the other communities of Nunatsiavut, Labrador’s Inuit territory. Record-setting temperatures and the least amount of ice in Canadian record-keeping may be extremes, but are on par with the experiences of Canada’s North, a region warming at twice the rate of the rest of the world.

“Our world is rapidly changing. It is something that keeps me up at night, and I think a lot of Inuit feel the same way,” Obed told CBC in a recent interview.

“This is real in a way that it may feel like it’s futuristic in other parts of the country.”

Obed also has insight, and a warning, to how complex responding to those monumental shifts can be.

He and other Inuit have been working for years to sound the alarm and take action within their own lands. Inuit Tapiirit Kanatami, the national organization representing Canada’s Inuit, released a climate change strategy in 2019, outlining ITK’s goals for Inuit Nunangat, the area encompassing Nunatsiavut, Nunavut, Nunavik in Quebec and Inuvialuit in the Northwest Territories and Yukon.

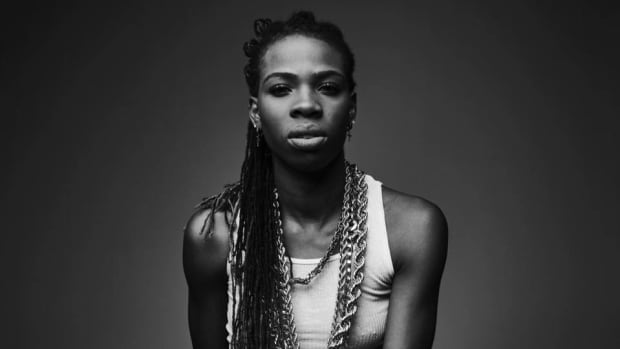

Now in his second term as ITK’s president, Obed is trying to turn that strategy a reality, an effort that he says requires the federal government to step up — and speed up.

“We want to be leaders in climate action. We want to also have Canada recognize the urgency that that our particular population is facing in relation to climate realities,” he said.

“Inuit Nunangat is changing rapidly. And if there aren’t investments in Inuit Nunangat directly for adaptation and mitigation to a higher magnitude than exists now, then we’re setting ourselves up for really difficult times ahead.”

Plans and stumbling blocks

ITK’s strategy is a policy document; that is, lengthy and dense.

But at its heart, it tackles climate change as an Inuit-led, societywide transformation. It has to be so, said Obed, because climate change’s effects are already everywhere. The thinning ice jeopardizes transportation routes, inhibits food gathering, and seeps into every corner of Inuit culture.

“It is hard to detach what we’re doing on climate change versus what we’re doing on food security now. It just seems it is, by necessity, kind of becoming part of the whole,” Obed said.

That approach, however, is butting up against the reality of bureaucratic red tape.

While the strategy received $1 million from the federal government when it was unveiled, a win for ITK, Obed said that money was spread thin over Inuit Nunangat, which comprises a third of Canada’s entire landmass.

“I think the federal government has done a good job of articulating the urgency of climate action and why it’s necessary. I don’t necessarily think the federal government has been able to provide supports in Inuit Nunangat the way in which we had hoped yet,” he said.

One ITK priority is trying to wean Inuit communities off diesel, a power source that is unreliable, expensive and polluting. Federal cash has been coming in, but not near what is required, Obed said. And the funding flaws in that diesel program are being seen elsewhere, with some communities receiving money for projects and others left out.

“It isn’t holistic and and it isn’t universal,” said Obed. He called the climate change file “really hard,” and that in order to implement the ITK strategy “upwards of 10 federal governments” need to come together.

WATCH | Natan Obed describes how daily life has changed, just in his own lifetime:

Natan Obed describes how daily life has changed, just in his own lifetime 2:35

Working with the federal government has resulted in some success for the Inuit: Obed pointed to suicide prevention and eliminating tuberculosis as two places the sides have made strides. But working through climate change has proved to be a different beast, and even small victories get dragged down in the details.

“It’s usually with terms and conditions that we have to figure out how to manoeuvre through in a way that isn’t simple,” said Obed.

“There is a lot of time that we spend at ITK and in Inuit Nunangat land claim regions trying to figure out how to take advantage of piecemeal programs that then takes us away from working on the larger picture and trying to to implement a larger picture.”

Time is of the essence

Time is a precious commodity in these circumstances, with the ice literally thinning underfoot.

“Climate change is rapidly rendering our knowledge invalid,” Obed said, with oral knowledge prior to the 1970s not able to be used in the same way, such as how to navigate on the ice that serves as Inuit highways for much of the year.

There’s also a sense of loss at witnessing the changes in the surrounding environment, and the weight that knowing while humans may be able to adapt, some species, such as caribou or Arctic char, might not be able to do the same.

“These are the types of things that we are confronting as a society,” he said. “And it’s a really difficult time to navigate through.”

It could be easy to despair at this point. Obed, with two young sons growing up in Iqaluit, can’t wrap his head around what their world will look like when they reach his age.

But Obed said he still finds hope. “Inuit are resilient,” he said.

Add to that, active and engaged, particularly with scientific communities. The social enterprise SmartICE has won worldwide recognition for its marriage of Western science and Inuit knowledge that helps keep people safe. ITK announced earlier in May it is also embarking on a new research program with international partners to focus on changing Arctic ecosystems.

“The work that we do at the national level and the work we do engage in the international community helps tell that story, but also demands action,” Obed said.

Obed will continue to advocate, particularly on that international stage: he was part of the Canadian delegation to the United Nations 2015 summit that established the Paris Agreement, a global landmark for climate change. Barring any pandemic disruptions, he’ll be at the next edition of that conference, set for Scotland in the fall.

But even in those high-profile arenas, he said there’s still a lot of work to be done to elevate the voices of Indigenous people, who are often at the forefront of change, but not in the driver’s seat.

“There are a number of different peoples globally that are seeing the worst effects of climate change already. And it only makes sense to have our voices heard.”

Thin Ice is a special CBC series about the changing climate along Labrador’s north coast, and the Indigenous-led responses arising from it. Read more in this series here.